The most recent IPCC summary report (2023) says that current policies will bring us to a 3.2° C rise in global average temperature by 2100[1]. “We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator”, according to UN chief, Antonio Guterres.[2] Carbon trading, as framed in the Kyoto Protocol, remains the centerpiece of global climate policy. Part 1 of this blog tells a bit about how carbon trading came about, part 2 explains the ‘compliance market’, and part 3 sheds light on the ‘voluntary carbon market’.

Part 1- Market framing of climate action

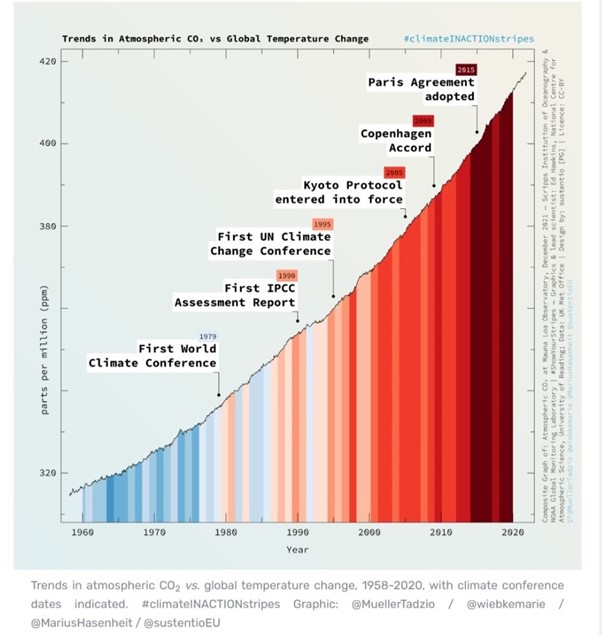

In the 1980’s, the science on the global warming effect of greenhouse gases was becoming increasingly clear. The Advisory Group on Greenhouse Gases was set up in 1986 by the International Council of Scientific Unions, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). In response to the US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) call for an international restriction of greenhouse gases, the Reagan Administration steered the creation in 1988 of the IPCC, an intergovernmental organization in which the influence of scientists is tempered by governmental interests.[3] In 1992, 154 nations signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) treaty confirming the intention to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and for ongoing scientific research, regular meetings, negotiations and future policy agreements.[4] The IPCC has issued reports since 1990 to the present which have increasingly emphasized the urgent need for action this decade (2020 – 2030).[5]

Two highly questionable premises

The world’s response to climate change was conceived at the international UNFCCC climate conferences. Hermann Scheer, the late German politician and founder of the European Association for Renewable Energy, EUROSOLAR, observed that ‘two highly questionable premises’ were the basis for the negotiations.[6] The first premise is that every nation should have similar obligations because greenhouse gas emissions are a global problem. What has become clear over the last 20 years is the opposite: that greenhouse gas emissions need to be cleaned up where they are emitted, and every nation needs a tailored approach, in line with its responsibilities and capabilities. The idea that pollution is global has permitted the misdirection of action on emissions from the pollution emitted in the global north to focus on various projects in the forests of the global south.

The second premise is that climate protection measures are an economic burden in which burden sharing must be achieved by consensus.[6] To the contrary, climate protection measures can stimulate the economy, and experimentation by pioneers needs to be encouraged to find the best solutions. Consensus brings the whole effort down to the lowest common denominator (see conceptual trap of consensus below). The consequences of these two premises will be discussed below.

First tiny step - Kyoto

The first implementation of measures under the UNFCCC was the Kyoto Protocol which was signed in 1997 and ran from 2005 to 2020. It was an agreement of 38 industrialized countries to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 2012 to a level 5.2 per cent lower than those of 1990.[7] Even in 1997, climate scientists knew that the Kyoto target was too small to slow the accumulation of greenhouse gases even temporarily.[8]

Kyoto avoidance option

Nevertheless, the United States introduced into the Kyoto negotiations a proposal that served to undermine even this weak target. The idea was to allow an industrialized treaty participant the option of not making reductions, by allowing them to contract emissions reductions more cheaply on a global market. This global market for carbon offsets (see Part 3) was institutionalized in the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM)

and the Joint Implementation (JI) framework in the Kyoto Protocol, and carries through to today, most recently in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

The justification for such a global market relies on the rationale that air pollution is global and can therefore be ‘cleaned up’ anywhere. This misses the fact that it is not currently possible to reduce emissions at scale by pulling them out of the air. To reach our goals, the emissions directly from the smokestacks in industrialized countries must be reduced. That is why this ‘global pollution’ rationale for the market is mistaken. Where there is smoke there is fire, but reducing some of the smoke does not extinguish the fire.

What is the goal?

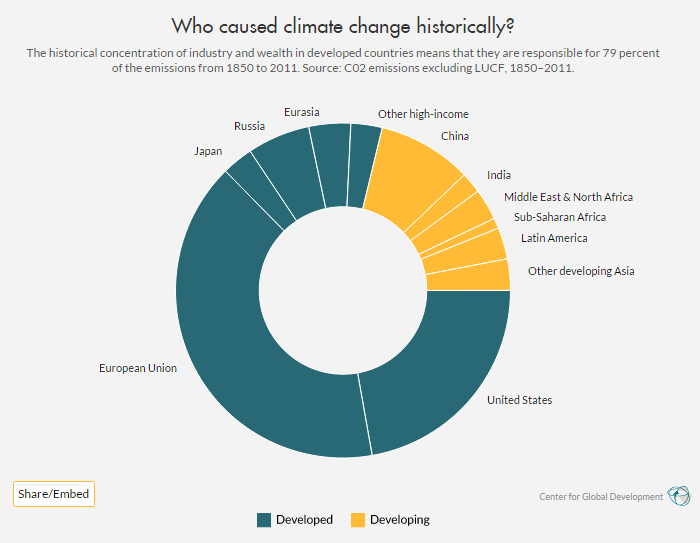

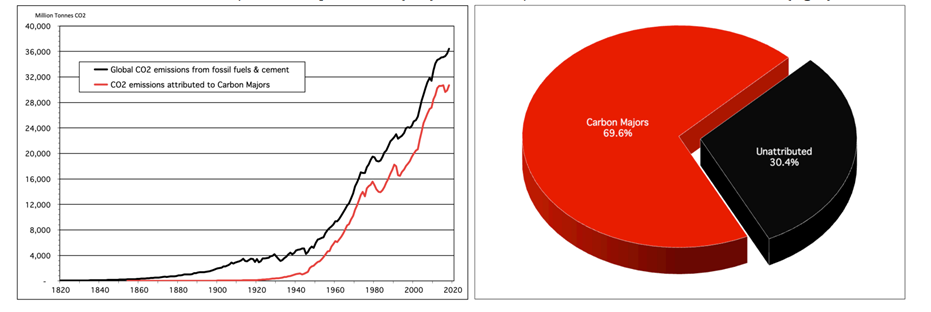

The Paris Agreement goals are to reduce emissions by 45% by 2030 and by 95% in 2050.[9] Once emitted, greenhouse gases affect the entire atmosphere. Nevertheless, it is known where and by whom greenhouse gases are emitted. Developed countries are responsible for about 80% of the historical emissions between 1850-2011.[10] (Figure 1) It is also known that only 108 companies are responsible for 70% of the emissions between 1820 to 2018.[11] ( Figure 2) In the period, 1965-2018, when fossil fuel companies knew the consequences of their emissions, 35% of all fossil fuel and cement emissions were caused by only 20 companies, with Chevron, BP, Exxon and Shell at the top of the list.[10] Without reducing the emissions of these ‘carbon majors’, there can be no

way to achieve the needed decrease in emissions. The global market system is an avoidance mechanism, one that enables major polluters to easily obtain credits to continue to pollute. Furthermore, these credits often do not guarantee actual emission reductions are taking place.[7] (see Part 3)

Consensus trap

Hermann Scheer writes that ‘the Kyoto Protocol was only agreed because it freed most countries (including China and India) from any obligation to act.’ He observes that ‘it is impossible to achieve a truly substantial agreement involving equal and concurrent obligations, because the circumstances [of the world’s countries] are too unequal.’[4] Instead, the need for consensus squashes ambition and forces the negotiations to aim for the lowest common denominator. Individual nations are discouraged from taking the initiative and addressing the climate with ‘pioneering actions’. Scheer cites a 2010 report by the German Scientific Committee of the German Federal Ministry that claims that countries investing in pioneering initiatives are punished because they pay for solutions that enable other countries to get a ‘free ride’.[4] Discouraging national action while insisting on consensus from the diversity of countries creates a hopeless paralysis in global climate policy, which was already visible in 2010.[4]

Market framing delays and avoids action

The market framing of the emissions mitigation action has misdirected action away from the carbon majors. Furthermore, by insisting on consensus and equal effort by all countries, pioneering actions have been discouraged. In these ways, the Kyoto framing of international climate action has blocked alternatives. In Parts 2 and 3, the two types of market solutions are explained with a discussion of their effectiveness to date.

[1] The IPCC just published its summary of 5 years of reports – here’s what you need to know – Climate Champions (unfccc.int)

[2] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/11/7/world-on-highway-to-climate-hell-un-chief-guterres-tells-cop27#:~:text=%E2%80%9CWe%20are%20on%20a%20highway%20to%20climate%20hell,and%20Development%20%28OECD%29%20hitting%20that%20mark%20by%202030.

[3] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – Wikipedia

[4] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – Wikipedia

[5] NRDC, (2023, April 14), IPCC Climate Change Reports: Why They Matter to Everyone on the Planet, https://www.nrdc.org/stories/ipcc-climate-change-reports-why-they-matter-everyone-planet#sec-latest

[6] Hermann Scheer, The Energy Imperative, Earthscan, 2012, translated from Der Energethische Imperativ, Verlag Antje Kunstmann, 2010

[7] Gilbertson, T. and Reyes, O., Carbon Trading: How it works and why it fails, 2009,untitled (daghammarskjold.se)

[8] Malakoff, D. (1997). CLIMATE CHANGE: Thirty Kyotos Needed to Control Warming. Science, 278(5346), 2048–2048. doi:10.1126/science.278.5346.2048

[9] United Nations Climate Action, Net Zero Coalition | United Nations

[10] Center for Global Development, (2023) Developed Countries Are Responsible for 79 Percent of Historical Carbon Emissions, Developed Countries Are Responsible for 79 Percent of Historical Carbon Emissions | Center For Global Development | Ideas to Action (cgdev.org)

[11] Climate Accountability Institute, (2020, December 9), Update of Carbon Majors 1965-2018, https://climateaccountability.org/pdf/CAI%20PressRelease%20Dec20.pdf